|

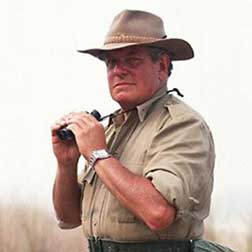

| John Blashford-Snell |

First Steps

Born in 1936, John was educated at Victoria College, Jersey and subsequently entered The Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst. He served for 37 years in the Army and saw active services in many areas. His family roots lie in Jersey where his grandfather was a sea captain. His father was an Army Chaplain and his mother is well remembered for her care of animals as well as the people of their parishes. JBS grew up amongst a menagerie of wounded and orphaned wildlife which generated his own interest in conservation. He married Judith in 1960, they have two married daughters and live in Dorset.

Youth and Exploration

In 1969, following the success of the Blue Nile Expedition, JBS and his colleagues formed the Scientific Exploration Society, their aim being "to foster and encourage scientific exploration worldwide". The SES became the parent body for many worldwide ventures with the support and involvement of HRH The Prince of Wales.

Inspired by the spirit of Sir Frances Drake's voyage 400 years ago, JBS poured his energy into raising funds and selecting a team to run Operation Drake. From 1978 to 1980 projects were organised for 400 young people from 27 nations working with scientists and servicemen in 16 counties. Operations were run from the Eye of the Wind, a 150-ton British brigantine which circumnavigated the world providing a floating base and laboratory for their scientific work.

As a result of the success of this venture, The Fairbridge Drake Society (now part of the Princes Trust) was formed to help disadvantaged young people and subsequently, at the request of the Government and many organisations, a much larger global youth programme was organised. In 1984 JBS launched Operation Raleigh and by 1992 over 10,000 young men and women from 50 nations had taken part in challenges and worthwhile global expeditions, returning home as true young pioneers intent on putting something back into their own communities.

In the interim, in the wake of the urban riots in 1981, JBS set up a special army unit in the Scottish Highlands named The Fort George Volunteers, designed to give the young a greater sense of purpose and responsibility. In the space of a year several thousand youngsters, many from Britain's inner cities, were put through a series of tough, exciting exercises. Places for these and his other ventures were extremely competitive and the method used to assess the potential and calibre of young people became a blueprint for many other youth-orientated organisations.

In 1993 he became Chairman of a £2.5 million appeal to establish a unique centre to provide vocational training and guidance for the young of Merseyside. It is now open and proving to be a great success. Later he helped to set up the Liverpool Construction Crafts Guild to promote the training of skilled craftsmen in Liverpool.

Adult Exploration Opportunities

In 1991 JBS retired from the Army and as Director General of Operation Raleigh. Following requests to use his wealth of experience to provide similar opportunities for mature people, he organises and leads many science and community aid based ventures, taking people of all ages to remote areas of the world.

The Present

He assists less privileged youngsters and is concerned with the development of opportunities for youth. He is also a Patron of the Moorlands Community Development in Brixton and assists the Calvert Exmoor Trust in its work with physically handicapped young people. From 2004 to 2009 JBS directed the Trinity Sailing Foundation appeal that raised funds to give disadvantaged youngsters short sea training courses. He continues as Vice-President.

He has founded Operation New World, a programme providing field experience for environmental students and is President of the Scientific Exploration Society, which now approves expeditions worldwide. Since 1998 he has led the major Kota Mama expeditions, involving the navigation of South American rivers with traditional reed boats, seeking archaeological sites and providing support for the people, fauna and flora of remote regions. JBS also helped to set up Just a Drop, the World Travel Market's charity that provides funding for water projects in the developing world and he is now its President. He is also a fervent supporter of British Army charities and a Vice President of the St George's Day Club.

His interest in unsolved mysteries and wildlife has led him to be elected Life President of the Centre for Fortean Zoology and succeeds the late Dr Bernard Heuvelmans. He has a special affection for voles and is President of the Vole Club.

In recent years JBS has been concentrating on exploration in little known areas of South America and in 2009 he led another meteorite quest in Bolivian Amazonas.

JBS is an international ambassador for the famous Zenith watch company of Geneva who supplied watches for the epic Darien Gap Expedition in 1972. JBS is a brand ambassador for Zenith watches and a limited edition of 500, named "Zenith, El Primero Blashford", has been produced as a tribute to him.

Source: http://www.johnblashfordsnell.org.uk/6.html

Another example of a former soldier who had, or rather has, a compassionate attitude towards animals. Which demonstrates to us that the stereotype of the hard-drinking, action-loving, soldier is an inaccurate one.

P.S. Again thanks to an anonymous commentor for suggesting Mr Blashford-Snell.

[End.]