It is also partly intended to show images, be they paintings, statues or photographs of the countenaces of men of yore. Because, quite frankly, many men wear the countenances of women these days: smiling, smirking, cooing, rolling their eyes, looking smug etc. It's a sign of the times, and by showing some images of men from the past, I hope to show some modern men why looking surly, frowning and giving hard-ball stares at people is something to do, something to practice.

|

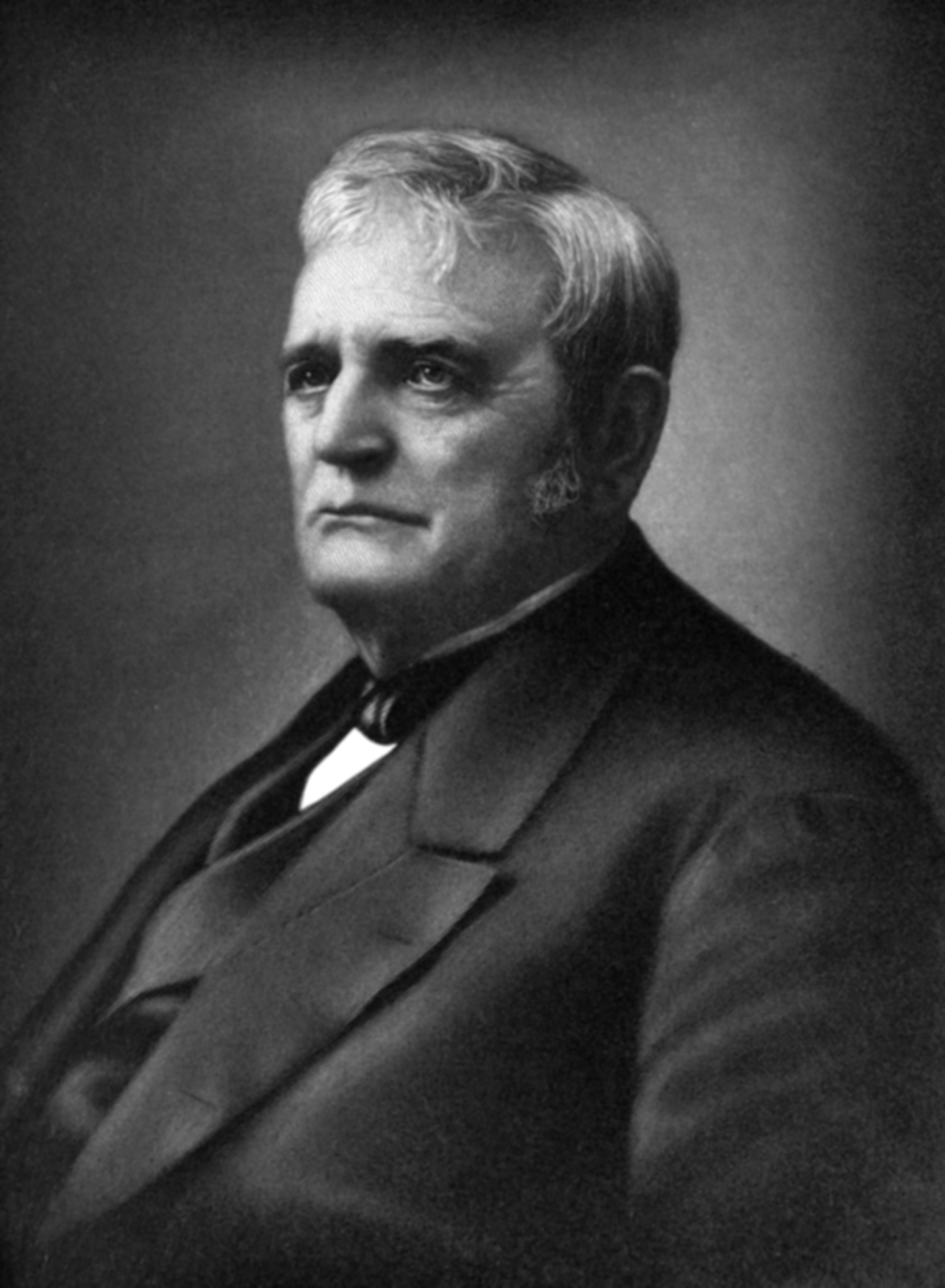

| John Deere |

John Deere: A Biography

When John Deere crafted his famous steel plow in his blacksmith shop in 1837, he also forged the beginnings of Deere & Company—a company that today does business around the world and employs more than 50,000 people.

As we celebrate the 209th anniversary of the birth of this enterprising pioneer, it’s appropriate to look back at his life and the legacy he left.

John was born in Rutland, Vermont, on February 7, 1804, and raised in nearby Middlebury. He was just 4 years old when his father was lost at sea, leaving his mother, Sarah Deere, to raise John and his five brothers and sisters. Due to his family’s near poverty lifestyle, John received no more than the simplest of education.

In an effort to help out his mother, and without her knowledge, John took a job in his early teens with a tanner, where he ground bark in exchange for a small amount of money, a pair of shoes and a suit of clothes.

At the age of 17, in 1821, John left home, with his mother’s blessing, to become an apprentice to a prosperous blacksmith of notable reputation in Middlebury, Captain Benjamin Lawrence. For the four-year apprenticeship, John was paid a $30 stipend the first year, and an additional $5 for each of the remaining years. He also received room and board and a set of clothes. Perhaps more valuable, John gained guidance from the stern, yet skilled Captain Lawrence, who not only taught him blacksmithing, but likely filled the void left by the death of John’s father more than a decade earlier.

Completing his apprenticeship in 1825, an eager, young John Deere moved on to journeyman positions, where he honed his skills and learned first-hand that a blacksmith’s workmanship was his signature.

John likely performed a variety of blacksmith duties, from shoeing horses and producing pots, pans and skillets, to manufacturing farm implements such as hay rakes and forks. But the most common work of blacksmiths of that time was furnishing the ironwork for stagecoaches and mills.

It was during this period that John met Demarius Lamb, a young woman attending boarding school in Middlebury. Despite the differences in their backgrounds, the two were married in 1827. John was 23, Demarius, 22.

For the next decade, John and his growing family would move from town to town throughout central Vermont searching for steady work. There was no shortage of skilled blacksmiths in the area and competition was keen. At one point, John borrowed money to buy land and build his own blacksmith shop, only to have it destroyed by fire not once, but twice. He was forced to sell the property he had just acquired, putting his dream of proprietorship on hold for the time being.

The fires had left John deeply in debt and once again, in need of a stable income. It was the 1830s, and fellow Vermonters shared John’s economic woes. The state’s rich timberland had been cut down, land was losing value, and the formerly rich and protected soil was washed away by a series of disastrous storms. A grasshopper plague weakened crop yields. Making matters worse, the nation’s banking system was collapsing in what would become known as the “Panic of 1837.”

Searching for a fresh start, Easterners began fleeing West to the prairies of Ohio, Indiana and Illinois. A former employer of John Deere’s had settled in a small village on the Rock River in northwestern Illinois, named Grand Detour. On a return trip to Vermont to fetch his family, the man enticed John with tales of opportunity in the flat, expansive prairie.

Perhaps what finally made up John’s mind was a summons he received in November of 1836 to appear before a justice of the peace in the Village of Leicester. John owed a note for $78.76 and the lender wanted payment. John’s future, indeed, looked bleak. What should he do? Stay in Vermont and risk losing his land, or worse yet, face debtors prison? Or, leave his family behind while he got established in Illinois, made some money to pay his debts and then retrieve his loved ones?

John made the difficult decision to leave his family, including a pregnant wife and four children, and head West to seek his fortune. Traveling by canal boat, steamer and wagon, and with just $73 in his pocket, John made the several week trip to Grand Detour. Upon arrival, John rented land near the river, hastily built a small blacksmith shop and began receiving work in a few days.

It wasn’t long before he heard tales of frustration from the transplanted Vermont farmers, struggling to break the tough prairie sod. Their cast-iron plows that worked so well in the light, sandy New England soil, performed poorly in the sticky soil of the Midwest. Soil clung to the plow bottoms and had to be removed, by hand, every few steps, making plowing an arduous and time-consuming task.

Despite his difficulties in Vermont, John was an inventive and skilled blacksmith. He realized that a plow with a highly polished surface could clean—or scour—itself as it moved through the field.

One day, in 1837, John spotted a broken sawblade in the corner of a sawmill and asked the owner if he could take it back to his shop. There John Deere fashioned the world’s first successful steel plow, and in doing so, opened up the West to agricultural development.

It was time to send for his family. In late 1838, Demarius and the five Deere children embarked on the six-week journey west, primarily by covered wagon. Baby Charles, who would later succeed his father as president of Deere & Company, was cradled in the wagon’s feedbox.

Though he had neither the facilities nor financial resources to produce more than a few plows a year, John Deere soon realized his future success lay in the plow business rather than the blacksmith trade.

So John set to work building steel plows, constantly improving the design to set his product apart from the competition. He began taking on partners, to help finance his young company. Especially costly were the large shipments of steel he imported from England—the only place he could find the material at the time.

John impressed his early partners not so much with his inventiveness, but with his motivation, dedication and ability to solve problems.

In 1848, John Deere moved his operation to the enterprising, young town of Moline, Illinois, to lower his costs by taking advantage of better transportation and water power provided by the Mississippi River. Within a few years, production had reached 1600 plows a year and John was getting his own special steel, rolled to his specifications, from mills in Pittsburgh.

Many of these first plows were loaded on wagons and peddled throughout the countryside. Others were shipped by steamboat to river towns up and down the Mississippi. Teams and wagons were then dispatched to distribute the plows to merchants in nearby villages, as railroads did not yet extend west beyond the river.

It was during these early days of the company that John Deere laid down principles of doing business that are still followed today. Among them was his insistence on high standards of quality. “I will never put my name on a product that does not have in it the best that is in me,” he vowed.

One of John’s early partners would often chide him for constantly making changes in design, saying the work was unnecessary because the farmers had to take whatever they produced. John is said to have replied, “They haven’t got to take what we make and somebody else will beat us, and we will lose our trade.”

John made certain his oldest surviving son Charles (see photo at left) received the formal education he was denied, no doubt with an eye toward bringing him into the business. Young Charles was educated in a number of private Moline schools, went on to Iowa College in Davenport, Iowa, across the river, and then to Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois. He completed his formal education at the prestigious Bell’s Commercial College in Chicago, earning today’s equivalent of an MBA.

With his education completed, Charles joined the company as a bookkeeper in 1853, at the age of 16. Working his way through a variety of positions, Charles quickly earned a reputation as a keen businessman. This must have delighted John, as it allowed the father and son to both focus on what they did best—Charles handling the business, and John attending to the products and sales.

By 1858, John had turned over management of the business to Charles, who was just 21 at the time. This gave the 54-year-old John more time to devote to social and philanthropic causes.

In the early 1850s, John became interested in politics and agreed to be chairman of the county convention for the Whig party. When the Republican party was later formed, John quickly became an active member and a strong abolitionist during the emotional years of the Civil War.

John also led the efforts to bring a fire engine to Moline, co-founded the First National Bank and was a trustee of the First Congregational Church. He was well known for his generous contributions to local educational, religious and charitable organizations.

Although still officially serving as president of Deere & Company, John’s role in the business was minimal after the Civil War. He purchased a farm east of Moline in the early 1860s and raised registered Jersey cattle and Berkshire hogs. In 1865, his wife of 38 years, Demarius, died at the age of 60. The next year, John traveled to his native Vermont and married Demarius’s younger sister Lucenia.

Capitalizing on his political experience, John was elected the second mayor of Moline in 1873, in the throes of the temperance movement. Though a supporter of temperance, he helped pass a liquor license ordinance and received widespread criticism. Mayor Deere, however, was credited for constructing and repairing sidewalks and streets and replacing open drains with sewer pipe to prevent disease.

After his two year term was up, John was more than ready to leave the political mudslinging behind. He and Lucenia made frequent visits back to Vermont and escaped the Midwest winters with trips to Santa Barbara and San Francisco, thanks to the recently completed transcontinental railroad.

John Deere died on May 17, 1886, at the age of 82, at his spacious home Red Cliff, which overlooked the sprawling city he had built, now with more than 10,000 residents.

Moline fell into mourning. Deere & Company’s factories and offices, as well as others in the city were draped in black. Flags were hung at half-mast and many private citizens placed photographs of John Deere in the windows of their homes, framed by black curtains.

Three days later, more than 4,000 people stood in line at the First Congregational Church to pay their final respects. A funeral cortege consisting of company workers, police, mourners on foot and in 11 carriages, and the city’s mayor and city council then processed to Riverside Cemetery where John Deere was laid to rest.

So while the man himself was gone, his legacy lived on in a way he could have never imagined. His descendents or their spouses went on to lead the company John Deere founded for the next 96 years.

Deere & Company is guided today, as it has been from the beginning, by core values that were key to its early success: quality, innovation, integrity and commitment.

As John Deere first declared so many years ago, customers trust Deere & Company to deliver the best that is within them. That has become not only John Deere’s legacy, but the company’s purpose—to create an exceptional and sustained experience of genuine value for customers, employees and shareholders—a performance that endures

Source: http://nortrax.com/about/deere/index.html

John Deere faced set-backs early on in his life, losing his workshop twice to fire, and being thrown in prison for debt. Yet he was not discouraged or disheartened by these events, he carried on, persevered and didn't 'throw in the towel'. And his perseverance paid off. He developed a revolutionary piece of agricultural equipment that allowed formerly un-farmable lands to become planted and farmed.

Check out some of the other entries from the 'Men of Yore' series:

Ambroise Pare

Diogenes of Sinope

Samuel Colt

Joseph Bazalgette

Franz Achard

Daniel Boone

Philo Farnsworth

Gregor Mendel

James Cook

Diogenes of Sinope

Samuel Colt

Joseph Bazalgette

Franz Achard

Daniel Boone

Philo Farnsworth

Gregor Mendel

James Cook

[End.]

No comments:

Post a Comment